💖Motivation Meows💖

Hello, and welcome to the latest edition of The Black Cat.

As always, here is some Good Black News.

The applications for Glossier’s Black Business grant program are now open. It will award four businesses $50,000, and one grantee alum will receive $100,000. Apply by June 1st. The Biden-Harris admin announced more than $16 billion in support for HBCUs, and Terri Burns, known for being the youngest and first Black woman partner at GV, has launched her own firm, Type Capital. She plans to invest in early-stage companies.

This month, I’m reading: Chinatown by Thuân

This weekend, I can’t stop listening to: Feeling Good by Nina Simone, covered by Raye

💢From the Chatterbox💢

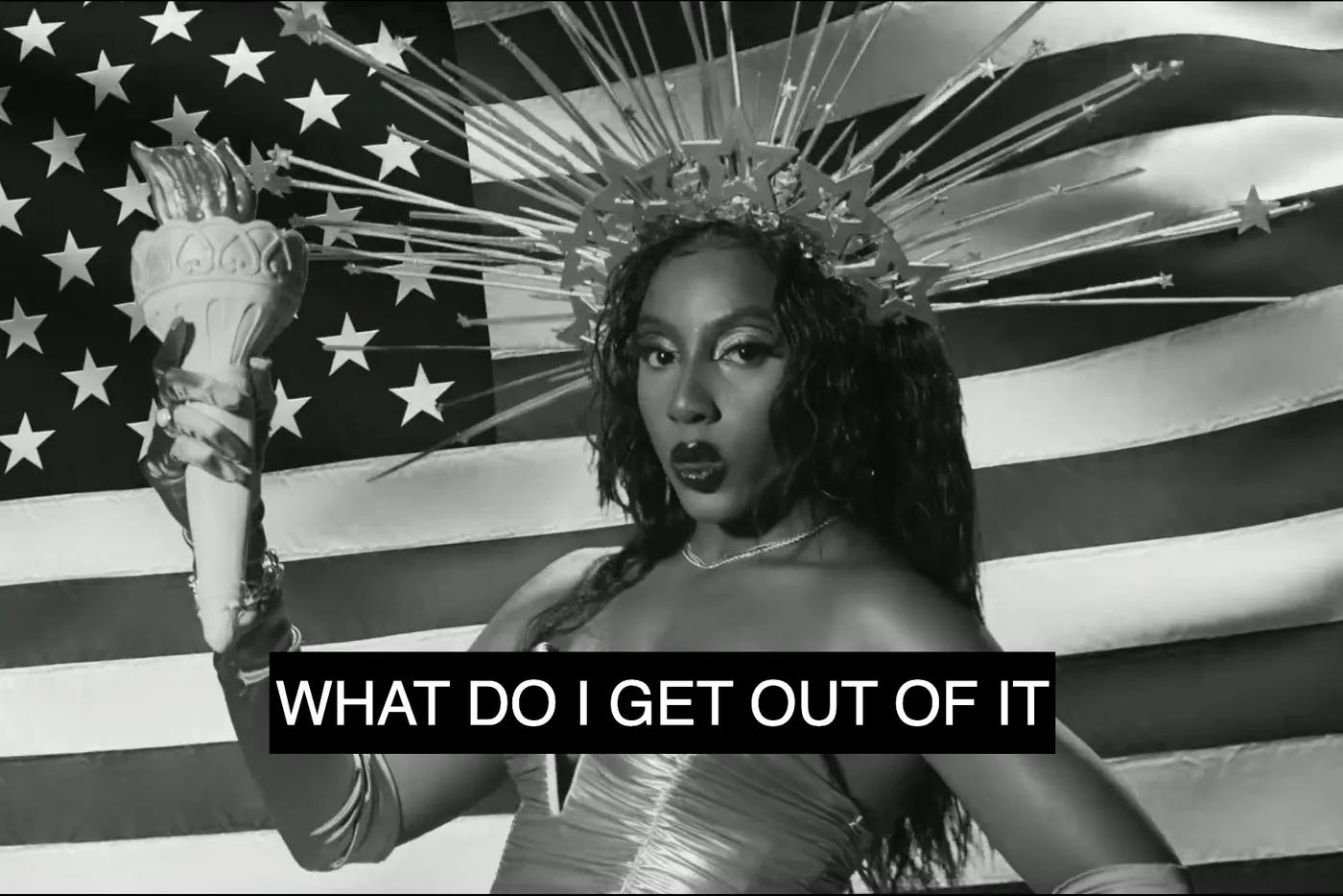

There is understandable discourse around Beyoncé’s use of the American flag in her latest album, Cowboy Carter. The loudest conversations have been about the displeasure of seeing it — or rather, seeing her embrace it so boldly — especially given African Americans' fraught relationship with America, its empire, and so forth.

The back-and-forth reveals the absolutely complicated, perhaps awkward, and unfortunate situation in which African Americans find themselves. After 400 years of being in America, the truth is we don’t really have another flag to call our own.

I chat to my non-Black friends about this sometimes, and sometimes they are like, ‘Just pick a flag in Africa; can’t you just find where you are from and take that flag.’ No. The whole point of being African American is that we don’t know where we were sold from. If I were to claim any flag today and move to a country in Africa, I would still find myself in a foreign land. James Baldwin wrote that after so long in America, we leave and find others within the Black diaspora only to realize we have more in common with those who enslaved us than from those in whom we were taken.

Even if I were to find my ancestral flag today, it would not change the fact that I, for the past 400 years, came from an American bloodline. The music, the religion, the folklore, the memories, and the history have all come to me from this land. Nina Simone sang of Mississippi, goddamn. The ties to the Africa we grasp for, like a baby longing for its mother, have long been severed. America is an imprint from which we will never be able to truly run, even if one day we make it back to the place we think of as home. If we are not allowed to have or find at least a little pride in the story of how far we’ve come, then what else are we supposed to feel? Shame? Humiliation? Nothing at all?

Given the conversation around Cowboy Carter, I started thinking about this more. I would ask people who said she shouldn’t have used the flag what flag she should have used instead. I saw responses about using the pan-African flag or something similar. That flag is fine but would not cut to the root of the matter here — that she’s American. I read an essay in The Guardian about how none of our ancestors truly wanted to build this country. How they tried to escape and destroy it. That the flag represents slavery. That we should stay true to Africa. That, of course, America owes us reparations, and that “hopefully, we are not so desperately flagless that we are willing to cling to an empire that is killing us, and many others around the world, for aesthetic pride.” The essay was interesting, and I think people should read it.

This is a messy topic, but I will try to hit on what I can. I’m African American, and my ancestors have been here for a loooonng time. I don’t think I am clinging to the Empire. I think after everything that has happened and everything this nation did to us, we have a claim to do what we please with that flag, including putting it on an album.

The question is, what are we embracing? There is yet a word to describe the web of contradicting, painful, and joyous threads that weave the American identity. Maybe it is just that, then, acceptance and recognition of whatever this is. I think it’s true that for every Black person who wants to leave, there is a Black person who wants to stay here, who just wants the best for the country, who just wants equality and a fair sense of self so they can move on with their day. The flag did represent slavery. We have protested against — and for the right to be loved by — it for decades with boycotts, marches, and bloodshed. I didn’t see Beyoncé embracing the flag as her co-signing the darkness of the past, but rather a nod to the survival of it. Something that said I’m still here, bitch.

I have always seen the past 400 years as part of American history, as stories that have become part of the flag. What would the flag be without the stories of the people whose nation it flies over? The flag, to me, is an all-and-then-some. It means what we want, when we want, how we want. This is the same flag that my ancestors fought against and the same flag they say they fought for when they went overseas as soldiers. The same flag we burn at every protest is the same flag I feel relief to see when I’m spending prolonged time abroad and the only thing I want is something familiar. Like pancakes or coffee. Its something that reminds me I am far from home. When you leave America, you realize you are indeed very American. Our ideas about one day joining a unified diaspora and sailing into one giant Africa are naive. I threaten to leave America all the time, and one day, I probably will. But ask me if I would ever give up my passport, and the answer would be hell no. I’m an American.

And I wouldn’t even describe myself as a prideful person, really. The writer of The Guardian piece rightfully pointed out that there is never really a good time to fully embrace American identity. It doesn’t change the fact that we have it, though. What else would we be? When I started thinking about what it means to be a part of the Black diaspora, I started feeling like, as an African American, I was like a little unsettled spirit in a home, searching for meaning and reasoning in this purgatory of a nation, and the chance to cross over into an afterlife of peace. I started coming to terms with the fact that there will never be ease. That if I found a new homeland in Africa along with new societal issues to call my own, there would always be a hole in my woven being that neither this homeland nor the next would ever be able to stitch. What will always be missing is the sense of true belonging.

So I kept thinking about the flag and what else we would fly on an album cover. This is the closest thing we have to home. I don’t see how anyone could look at what this nation has done these past few decades and separate African Americans from that narrative simply because the country has wronged us, too. The writer brought up a good point: can we separate Black pride from what this nation is doing? I don’t know. On an imperialist front, I don’t think you can shroud Black Americans from accountability — we fight in American wars and invade shores for the flag, too. During the Jim Crow era, our ancestors still signed up to go to war in the Pacific.

On a political and socioeconomic front, maybe we can skirt some accountability. We didn’t create these systems that oppress us, but in the modern era, we are also not completely uninvolved with them. I started to ponder, then, if the flag is only a symbol of our oppression, then indeed, why would we want to embrace it? But maybe the flag is more than an emblem of our oppression and one of our survival as African Americans, too. Maybe it’s all of those things with love and fear mixed into one. Every piece of us can be ripped into parts — on a racial, ethnic, cultural, and national level — but no matter what those detached components of us hold, all together, our story is still that of the flag and then some.

Culturally, we are intertwined. African American culture is one of the biggest American exports. Our contributions to music—jazz, blues, rock, and country—have completely changed the world. So did our fight for civil rights, which inspired other movements across the world. All of this is the story of America. What other flag would we attach these stories to, and why should it be anything other than the one we live under? Our beginning may have started in a different nation, but after 400 years, our blood has built a new one. Even the Black racial groups in America are American — the most basic of which is the mixture of Native American, African, and European, a blend, for better or worse, created here under that flag. I started thinking that no matter what reality we write for ourselves or what history we choose to retell, nothing at the heart of it could erase the relationship we have with that flag. It’s a tragic duet.

So what do we do with this thing that represents the dark and the light of our existence? This stressful, painful, peculiar existence that has kept us captive for so long, leaving us with an aching so heavy it could sink ships. If we were to all flee America, where would we go? Where in Africa? To which country, to which tribe, and speak what language? If people want to be silly, joke around, and claim the flag to find joy in a Beyoncé album, then they should. I don’t want to give the credit of this nation solely to the enslaver. Everything they did to us is tied up in that flag, which is why it means something when we burn it. But everything we are is also in that flag, which is why it means something when we fly it.

As a Southern, I actually liked seeing Beyoncé have the flag in her hands. Note that the whole flag doesn’t even show on the cover, only a part of it, just enough of it, really. I know the Confederate flying racists I went to school with now fly the American flag in place of the Confederate one. They would hate the idea that someone Black would claim this nation as their own. They would tell us to go back to Africa. That there is nothing here that is ours. I like the idea of a fuck you; it is ours, even if only some of it. It makes me feel like I have something. Like I am not this stateless, flagless, rouge woman trapped alongside others in this “settler project” without any roots in the earth. At the same time, I recognize it’s all too painful. There are so many layers, so many sticky tangles, and no one or right way to ease the hurt. I think Beyoncé’s album captured some nuance well: there is suffering, hope, survival, and acceptance. It’s a messy album for a messy group of people. There is “Blackbird,” “16 Carriages,” and “Yaya,” and if this nation does crumble, our stories and contributions will also be held up as a requiem for America.

Sometimes, I have dark thoughts that I would spend my whole life contemplating my existence. That I will never escape — or find ways to balance — the torrential pain associated with being a product of this nation’s sins. That nothing is acceptable for me to love in this country and that I would spend my whole life running, trying to find ease. It frightens me that no place might exist. But then those thoughts eclipse, and I hear the chirping of a spring day.

This conversation is endless, existential, and intricate — one we will have for the rest of our bloodlines. At times, I have no pride. I have all the pride. I have everything here and nothing at all. The writer asked if the Confederacy had won, would we proudly hold that flag, too? I don’t know. Should we wear star-spangled outfits or dashikis to Beyoncé’s concerts? Should we celebrate our forebears or, as the writer said, “honor different ancestors?” I don’t know about that either. What I do know is that I won’t deny others the satisfaction of at least giving a nod to the closest thing we have that tells the story of our time here. Whatever story we find that may be.

💫Kitty Talk💫

Here are some interesting articles I’ve read since we last met:

Washington Post, “DEI is getting a new name. Can it dump the political baggage?”

Financial Times, “South Africa’s ‘lost leader’ faces the end game”

The Atlantic, “The One Place in Airports People Actually Want To Be.”